Medications for Lupus

Jodi L. Norton, B.A. Columbia College in the city of New York, NY

President & Co-Founder of L.I.F.E.

And

Jacqueline Saunders Ferris State University School of Pharmacy

2014 L.I.F.E. Scholarship Recipient, Member of L.I.F.E.’s Honorary Winner’s Program & 2015 L.I.F.E. Degree Completion/Scholarship Renewal Program

© L.I.F.E. Publications Inc.

Medications used to treat lupus help decrease symptoms and disease progression. Treatments may be used in combination with other medications, based on symptoms specific to each patient. It is optimal to use the least amount of medication to prevent disease flares, control symptoms, and reduce inflammation.

This section provides a comprehensive list of medications (by class of drug) used to treat lupus. Each drug is listed according to their brand and generic names in an easy to understand and review format of charts and tables. A brief history is provided, purposed mechanism of action, symptom indication, adverse affects, interesting facts along with tips, reminders and specific warnings. Since lupus is most common during the prime of life—the child-bearing years—all medications are classified for safety during pregnancy. Many of these medications also treat a variety of diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, cancer, and other conditions. All medications are associated with risks and benefits, so it is important to find a regimen that is right for you.

Many lupus patients will use long-term therapy to maintain disease remission or lesson “flares” (an increase in disease activity). Severe cases of lupus can be life-threatening and should be treated with more aggressive treatment options. For less severe cases, patients may use medication intermittently to control their disease. Lupus is a disease that affects each patient differently, but tends to repeat itself. Therefore, it is important to be mindful of what triggers your lupus, so you can avoid them in the future. In treating lupus, one of the many goals is to increase the quality of life for patients through both mainstream medicine and integrative modalities of treatment, like massage, pet therapy, guided imagery, yoga, among others.

When dealing with a chronic illness, always aim to follow your recommended health-care plan. Encourage yourself to be proactive in your disease. Establishing a good relationship with your healthcare provider helps improve communication, trust, and outcomes. Disease progression can be decreased by maintaining a tolerable amount of daily activity, allowing for periods of rest, having a positive support system of family and friends, making healthy lifestyle choices, and implementing an anti-inflammatory diet.

Living with lupus is challenging, but remember that you are not alone. There are many other patients who have lupus. Stay positive and view your lupus as a teaching tool to learn more about yourself—an opportunity for personal growth. Learn to be spontaneous on a good day! Reach out to a positive support system when needed and take one day at a time. Schedule regular check-ups, comply with medication regimens as directed by your rheumatologist and address any concerns upon your next visit. Although lupus cannot yet be cured, many patients can lead normal lives with the right medication regimen.

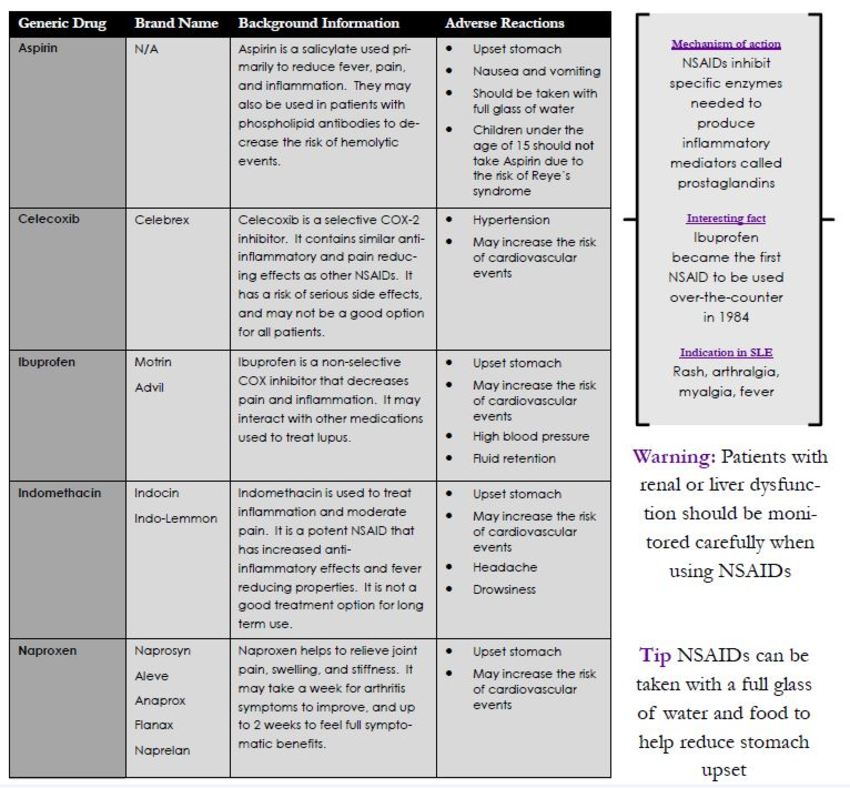

NSDAIDs (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs)

NSAIDs work to relieve signs of inflammation and mild-moderate pain. Most patients have no trouble taking NSAIDs, and they are commonly used for both acute and chronic health issues. Low dose NSAIDs help to provide pain relief, while higher doses are needed to reduce inflammation. Long term NSAID use carries an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, heart attack, and stroke. These events may occur with or without symptoms. Make sure to notify your primary care physician if you currently take anti-coagulants, aspirin, corticosteroids, or other NSAIDS.

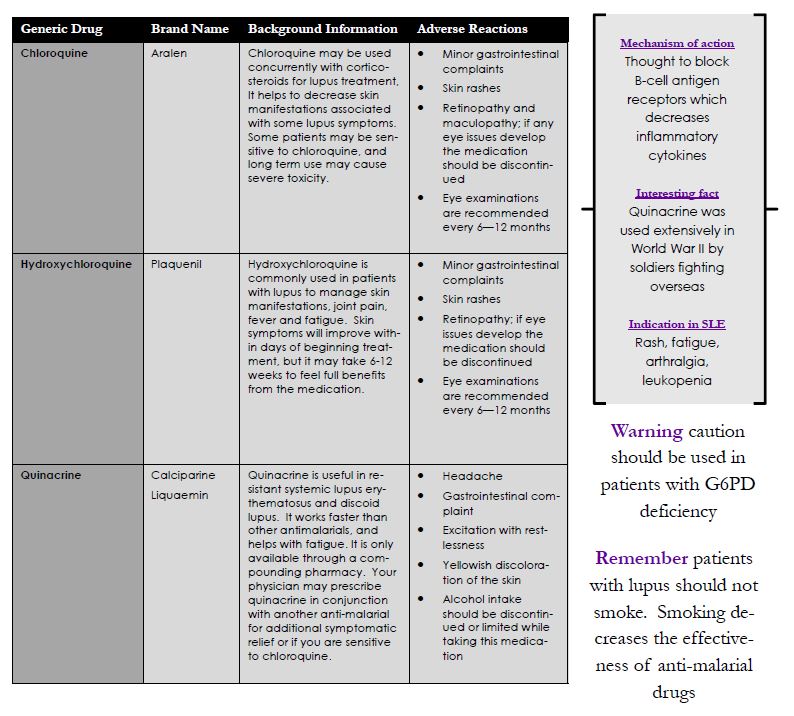

Antimalarials

Antimalarial drugs have numerous benefits for treatment in lupus. They are a part of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and help to effectively decrease autoantibody production in lupus, reduce the risk of flares, joint pain, and skin issues. Antimalarials have a low risk of serious side effects so patients may use them for long periods of time. Vision changes may occur in some patients so it is important to have regular eye examinations. These drugs usually take several months for full systemic benefits.

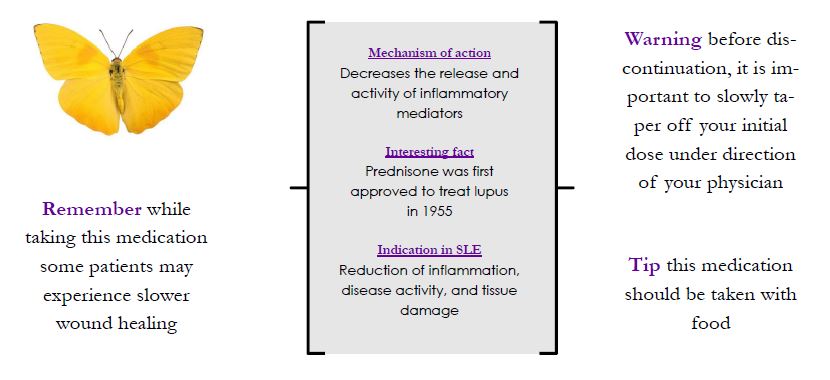

Oral Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids effect the production of cortisol in the body. They are included in the category of DMARDs, and used as a common maintenance medication in lupus because they work quickly to fight inflammation and suppress diseases activity. Due to side effects often associated with use, physicians prescribe the lowest dose tolerable to reduce symptoms. Unwanted side effects from steroid use include an increased risk of infection, hyperglycemia, weight gain, mood changes, increased blood pressure, and increased risk of osteoporosis. When discontinuing this medication, under the direction of a physician, it is important to slowly taper off of your initial dose. Depending on the purpose of treatment, steroids are available to be taken orally, topically, or by injection. If symptoms do not resolve, corticosteroids are frequently taken in conjunction with NSAIDs and/or anti-malarials.

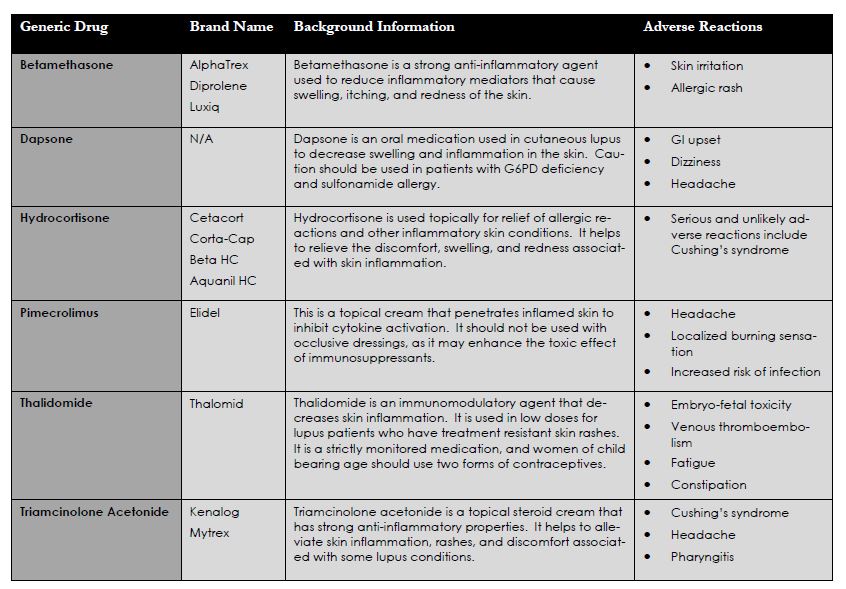

Topical Corticosteroids and Skin Treatments

Topical corticosteroids are used for local and some systemic relief of inflammatory skin issues. Many patients with lupus develop skin manifestations, especially after UV or prolonged fluorescent light exposure. Photosensitivity reactions may trigger flares, rashes, and other disease symptoms. These medications have fewer systemic side effects than oral corticosteroids, however long term use can still cause unwanted side effects similar to oral corticosteroids. These drugs are often used in conjunction with other immunosuppressive medications.

Immunosuppressive Drugs

Immunosuppressive medications help to control inflammation in moderate to severe cases of lupus that are not controlled with other medications or if major organs are involved. Some of these medications are in the treatment of some cancers, organ transplants, and other autoimmune diseases. They are DMARDs that work to suppress an overactive immune system, and many are composed of cytoxic agents so side effects may be of concern. With a lowered immune system patients are at an increased risk of infection. These drugs can be usedin conjunction with or after corticosteroids have been unsuccessful in controlling lupus symptoms.

Biologic Drugs

Biologics are a newer class of drugs that have revolutionized the way diseases are treated. They target a specific cell or antibody of interest to help suppress the immune system and reduce inflammation. By isolating the targets from natural sources, biologic medications can be processed into small molecule drugs to be used for a variety of different diseases. This includes cancer and autoimmune diseases. In patients with lupus, biologic medications are typically used after corticosteroids, anti-malarials, and one-or-more immunosuppressive drug have been unsuccessful in controlling symptoms.

These medications should not be used in conjunction with other biologic drugs. While taking any biologic drugs, live vaccines should be avoided. Before taking a biologic medication you should be aware of the risks associated with use. Serious risks include hypersensitivity leading to anaphylactic shock and an increased risk of opportunistic infections. A few biologic drugs also carry the risk of developing a rare, usually fatal viral infection called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). While the risk of developing PML is considerably low, it is advisable to discuss with your doctor about all potential side effects of the biologic drug before use.

While taking any biologic drug, all new symptoms should be reported to your rheumatologist. The benefits of taking a biologic drug should outweigh the consequences. These medications are not taken everyday, and they are given as an infusion about every 4-8 weeks. Most patients take a biologic drug for a longer period of time, with the goal of decreasing use after disease activity has decreased. These medications are very expensive due to the tedious production process, purification, and contamination prevention through sterile procedures. Some drug companies offer rebates and discounts for patients who may be unable to afford the medication. Contact the drug company directly or talk to your doctor about promotional opportunities that may benefit you.

WARNING: Many of the new biologic drugs have improved the quality of life for many patients. However, there are serious risks associated with these medications. The most dangerous complication in PML. It is rare but a serious and life threatening brain infection. Your chance of getting PML is higher if you are treated with other medications that weaken your immune system. PML can result in death or severe disability. If you notice any new or worsening medical problems such as memory loss, trouble thinking, dizziness or loss of balance and difficulty walking or talking among other symptoms.

Anticoagulants

Anticoagulants are medications used to decrease a patients risk of developing blood clots. Patients with lupus may have phospholipid antibodies present, which increases their risk of developing serious blood clots. Patients with this risk should avoid oral contraceptives, hormone treatments for women, and smoking. Tolerated body movement is recommended in conjunction with blood thinners. With the proper treatment and monitoring most patients will not have issues with blood clots occurring.

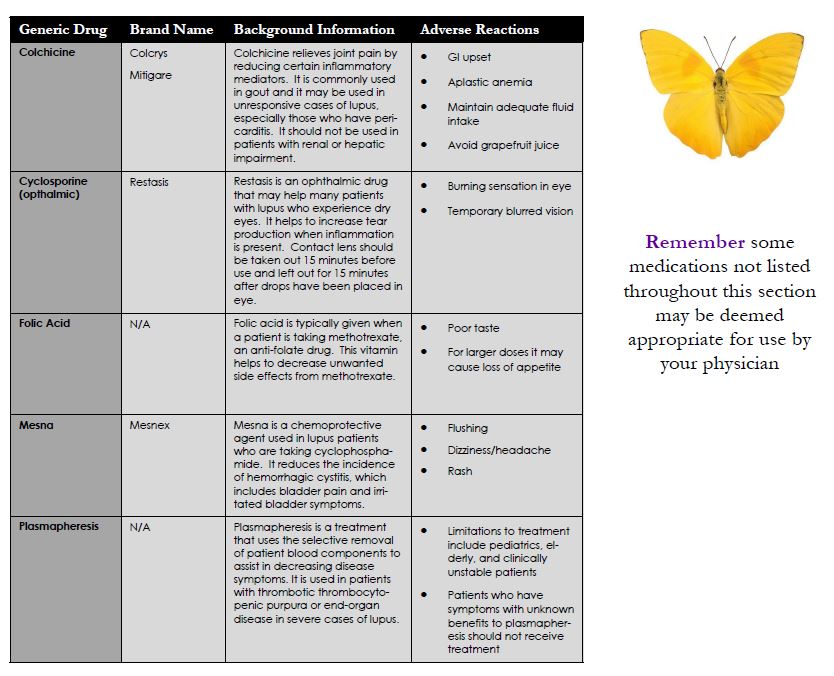

Other Treatments

This is a list of treatments that are used to reduce specific symptoms of lupus. Although these treatments are not all commonly used, they may be useful for some patients. Lupus is a unique disease in which it causes different symptoms in each patient. By working with your physician, and being open to what is available you may find the best available options for you to use as treatment that are tailored to your specific symptoms.

Medications Causing Drug Induced Lupus

A list of medications are known to have the risk of developing drug-induced lupus. Drug induced lupus encompasses similar symptoms that many lupus patients experience throughout the course of their disease includingfever, weight loss, skin manifestation, arthritis, kidney involvement, positive ANA, positive lupus antibodies, and low complement levels. Symptoms typically resolve after discontinuation of the medication.

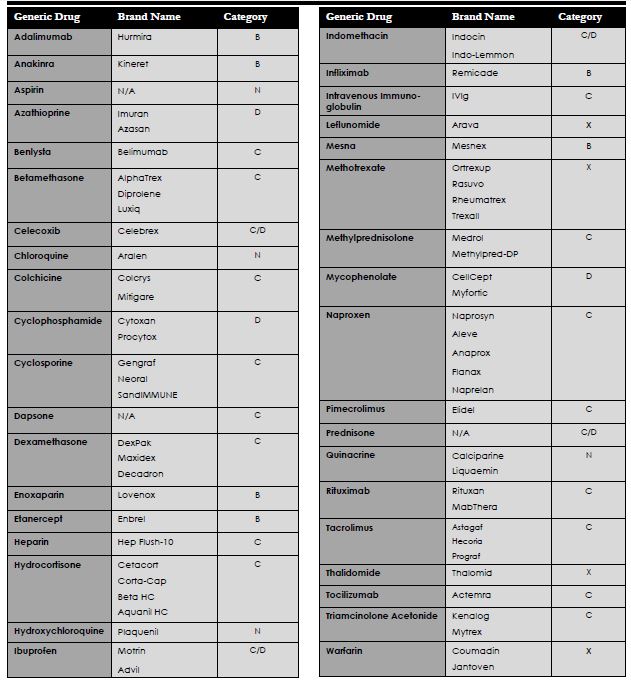

Medications for Pregnancy

Pregnancy and lupus are of common concern for women of childbearing age. Patients should be in remission for at least 6 months or have a good control on symptoms before trying to conceive a child. Many of the medications used to control lupus symptoms are not safe for use during pregnancy, however there are options to switch medications during gestation making it still safe for the mother and baby. Corticosteroids and plaquenil are examples of medications that are typically okay for use. Medications used in pregnancy are classified by the FDA according to the risk of adverse effects on the fetus. Any medication with pregnancy X should use two forms of contraceptives while using the medication.

¨ Class A: Well controlled studies have not shown any risk to the fetus within all three trimesters

¨ Class B: Studies in animals have not shown risk to fetus and no adequate studies have been conducted in women

¨ Class C: Animal studies have shown adverse effects on fetus and no well controlled studies have been conducted in women

¨ Class D: There is positive evidence of human fetal risk based on investigational data or studies in humans; potential benefit may warrant the use of a particular drug in pregnant women despite these risks

¨ Class X: Studies in animals or humans have demonstrated fetal abnormalities and the risks involved outweigh potential benefits in pregnant women

¨ Class N: FDA has not yet classified the drug

It is recommended that patients with lupus plan their pregnancies. Contraceptives may be used to prevent an unplanned pregnancy due to the fetal risk of adverse reactions from many medications used in lupus. Oral contraceptives may help to reduce corticosteroid osteoporosis, cyclic activity of SLE, manage endometriosis and ovarian cysts. These are not medications to use in patients with unstable symptoms, anti-phospholipid antibodies, nephrotic syndrome, or thrombosis risks. Depo is another option for contraceptive use that uses only progesterone, and has no adverse effects in lupus patients. It may increase the risk of osteoporosis after 2 or more years of use. Lastly, intrauterine devices (IUD) are contraceptives that have a low rate of failure and last between 5-10 years, depending on what type of device is used.

Patients with any complications during pregnancy, increased disease activity, or patients with positive phospholipid antibodies will be referred to a high-risk OB-GYN. Phospholipid antibodies put a women at risk for miscarriages, unexpected vascular clotting, and pre-term deliveries. Lupus flares may be more common during pregnancy, however arthritis flare ups are typically less common. It will be expected to have routine check-ups every 4-6 weeks with both your rheumatologist and OB-GYN during the duration of your pregnancy to make sure that the disease is well-controlled and that no complications arise.

© L.I.F.E. Publications Inc.

References

1 AHFS Drug Information. American Society of Health Systems Pharmacists. 2015.

2 Aringer, M., Burkhardt, H., Burmester, G., et al. (2012). Current state of evidence on “off-label” therapeutic options for systemic lupus erythematosus, including biological immunosuppressive agents, in Germany, Austria and Switzerland--a consensus report. Lupus. 21(4): 386–401.

3 Baer, A., Witter, F., & Petri, M. (2011). Lupus and pregnancy. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 66(10): 639–53.

4 Bengtsson, C., Andersson, S., Edvinsson, L., et al. (2010). Effect of medication on microvascular vasodilatation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology. 107(6): 919–924.

5 Bernatsky, S., Peschken, C., Fortin, P., et al. (2011). Medication use in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of Rheumatology. 38(2): 271–274.

6 Bernatsky, S., Joseph, L., Boivin, J., et al. (2008). The relationship between cancer and medication exposures in systemic lupus erythaematosus: a case-cohort study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 67(1): 74–79.

7 Betamethasone valerate cream, lotion, ointment [prescribing information]. Melville, NY: Fougera: July 2013.

8 Burmester, G., Panaccione, R., Gordon, K., et al. (2012). Adalimumab: Long-Term Safety in 458 Patients From Global Clinical Trials in Rheumatoid Arthritis, Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis, Ankylosing Spondylitis, Psoriatic Arthritis, Psoriasis and Crohn's Disease, Ann Rheum Dis.

9 Burness, C. & McCormack, P. (2011). Belimumab: in systemic lupus erythematosus. Drugs. 71(18): 2435–44.

10 Calixto, O., Franco, J., & Anaya, J. (2014). Lupus mimickers. Autoimmunity Reviews.

11 Carneiro, J., & Sata, E. (1999). Double blind, randomized, placebo controlled clinical trial of methotrexate in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of Rheumatology. 26(6): 1275 – 1279.

12 Clowse, M. (2010). Managing contraception and pregnancy in the rheumatologic diseases. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 24(3): 373–85.

13 D’Cruz, D., Khamashta, M., & Hughes, G. (2007). Systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 369(9561): 587–596.

14 Dall’Era, M. (2011). Mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 23(5): 454–8.

15 Dall’Era, M., & Chakravarty, E. (2011). Treatment of mild, moderate, and severe lupus erythematosus: focus on new therapies. Current Rheumatology Reports. 13(4): 308–16.

16 Dammacco, F., Della Casa Albeighi, O., Ferraccioli, G., et al. (2000). Cyclosporine-A plus steroids versus steroids alone in the 12-month treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. International Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Research. 30(2): 67– 73.

17 Dennis, G. J. (2012). Belimumab: a BLyS-specific inhibitor for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 91(1): 143–9.

18 Drug Facts and Comparisons. (2015). Clinical Drug Information, LLC.

19 Elidel (pimecrolimus) [prescribing information]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp: April 2014.

20 Fabbri P, Cardinali C, Giomi B, et al. (2003). Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus: Diagnosis and Management. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 4(7): 449-65.

21 Figueiredo-Braga, M., Mota-Garcia, F., O’Connor, J., et al. (2009). Cytokines and Anxiety in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) patients not receiving antidepressant medication: A little-explored frontier and some of its brief history. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1173: 286-291.

22 Gengraf (cyclosporine) [prescribing information]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; February 2013.

23 Generali, J, & Berger C. (2006) Review Tips. In Generali J., Berger C. (eds), quick review: Pharmacy, 13e.

24 Griffiths, B., Emery, P., Ryan, V., et al. (2009). The BILAG multi-centre open randomized controlled trial comparing ciclosporin vs azathioprine in patients with severe SLE. Rheumatology. 49(4): 723 – 732.

25 Hahn, B., McMahon, M., Wilkinson, A., et al. (2012). American College of Rheumatology Guidelines for Screening, Treatment, and Management of Lupus Nephritis. Arthritis Care Res. 64(6): 797-808

26 Hensley, M., Hagerty, K., Kewalramani, T., et al. (2009). Clinical Practice Guideline Update: use of chemotherapy and radiation therapy protectants. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 27(1): 127-145.

27 Houssaiau, F., Cruz, D., Sangle, S., et al. (2010). Azathioprine versus mycophenolate mofetil for long-term immunesuppression in lupus nephritis: results from the Maintain Nephritis Trial. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 69(12): 2083 – 2089.

28 Humira (adalimumab) [prescribing information]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc; December 2014.

29 Imazio, M., Brucato, A., Trinchero, R., et. al. (2009). Individualized therapy for pericarditis. Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy. 7(8): 965–75.

30 Indocin (indomethacin) [prescribing information]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co Inc; February 2006.

31 Krikoria, S. (2006). Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Helms RA, Quan DJ, Herfindal ET, et al., eds. Textbook of Therapeutics: Drugs and Disease Management. 8th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 1767-87.

32 Leachman, S. & Reed B. (2006). The Use of Dermatologic Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation. Dermatol Clin. 24(2):167-97.

33 Leong, K,, Pong, L., & Chan, S. (2003). Why lupus patients use alternative medicine. Lupus. 12(9): 659–664.

34 Lexicomp. (2015). Wolters Kluwer Health.

35 Medline Plus Drug Information. (2015). National Institutes of Health.

36 Mesnex (mesna) [prescribing information]. Deerfield, IL: Baxter Healthcare Corporation; March 2014.

37 Micromedex Solutions. (2015). Truven Health Analytics, Inc. 2015.

38 Millet, A., Decaux, O., Perlat, A., et al. (2009). Systemic lupus erythematosus and vaccination. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 20(3): 236–41.

39 Monach, P., Arnold, L., & Merkel, P. (2010). Incidence and prevention of bladder toxicity from cyclophosphamide in the treatment of rheumatic diseases: a data-driven review. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 62(1): 9–21.

40 Mosca, M., Tani C., Carli, L., et al. (2011). Glucorticoids in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (29):S126-S129.

41 Needleman, P. & Isakson, P. (2009). The Discovery and Function of COX-2. Journal of Rheumatology. 24(49): 6-8.

42 O’Neill, S., & Isenberg, D. (2006). Immunizing patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a review of effectiveness and safety. Lupus. 15(11): 778–83.

43 Østensen, M., Khamashta, M., & Lockshin, M. (2006). Anti-inflammatory and Immunosuppressive Drugs and Reproduction. Arthritis Res Ther. 8(3): 209.

44 Patel, T. & Dhillon, S. (2013). Efinaconazole: First global approval. Drugs.73(17): 1977–1983.

45 Powers, D. (2008). Systemic lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus. Oral Maxillofacial Surg Clin N Am. 20(4): 651–62.

46 Product Information: Atabrine(R). Sanofi Winthrop Pharmaceuticals, NY, (discontinued), 1995.

Product Information: folic acid oral tablets, folic acid oral tablets. Trimarc Laboratories, Oklahoma City, OK, 2006.

47 Prograf (tacrolimus) [prescribing information]. Northbrook, IL: Astellas Pharma US Inc; February 2015.

48 Rahman, A. & Isenberg, D. (2008). Systemic lupus erythematosus. The New England Journal of Medicine. 358(9): 929–939.

49 Rainsford, K. (2003). Discovery, mechanisms of action and safety of ibuprofen. International Journal of Clinical Practice Supplement. (135):3–8.

50 Resman-Targoff ,B. (2014). Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Dipiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, et al., eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologc Approach. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. 1397-411.

51 Rubin, R. (2005). Drug-induced lupus. Toxicology. 209: 135–147.

52 Sato, E. (2001). Methotrexate therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 10(3): 162–164.

53 Shea, B., Swinden, M., Tanjong, E., et al. (2013). Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 5: CD000951.

54 Sugai, D., Gustafson, C., De Luca, J., et al. (2014). Trends in the outpatient medication management of lupus erythematosus in the United States. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 13(5): 545–552.

55 Tsokos, G. (2011). Systemic lupus erythematosus. The New England Journal of Medicine. 365(22): 2110–2121.

56 Vedove, C., Del Giglio, M., Schena, D., et al. (2009). Drug-induced lupus erythematosus. Archives of Dermatological Research.

57 Verbeeck, R. (1990). Pharmacokinetic Drug Interactions With Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 19(1):44-66.

58 Wallace, D. (2008). Improving the prognosis of SLE without prescribing lupus drugs and the primary care paradox. Lupus. 17(2): 91–92.

59 Walling, H. & Sontheimer, R. (2009). Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 10(6): 365-381.

60 Witt, M., Zecher, D., & Anders, H. (2006). Gastrointestinal manifestations associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. European Journal of Medical Research. 11(6):253–260.

61 Yoon, K. (2010). Efficacy and cytokine modulating effects of tacrolimus in systemic lupus erythematosus: a review. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010: 686480.